Dorimène Desjardins (1858-1932)

Desjardins ad

Dorimène Desjardins boarded at Notre-Dame-de-Toutes-Grâces convent for about 10 years. (1850-1950. Notre-Dame de Lévis)

Dorimène Desjardins boarded at Notre-Dame-de-Toutes-Grâces convent for about 10 years. (1850-1950. Notre-Dame de Lévis)

Marie-Clara Dorimène Roy-Desjardins was born on September 17, 1858, in Sorel. Her parents were Joseph Roy-Desjardins, a steamship captain, and Rosalie Mailhot. She was the fifth child in a family devastated by childhood diseases. Of the 11 Roy-Desjardins children, at least 5 did not reach adult age.

Dorimène studied in Lévis at a convent run by the Sisters of Charity, Notre-Dame-de-Toutes-Grâces (now the Marcelle-Mallet school). There, she learned to read, write and count. She also studied sewing, hygiene and home economics.

From 1866, she lived in Lévis with her maternal aunt, Louise-Clarisse Mailhot, and her uncle, Jean-Baptiste Thériault, an engineer. She probably moved in with them to attend the convent. Another one of their nieces, Philomène Thériault, also lived with them at the time. During a decade of schooling, Dorimène appears to have split her time between Lévis and Sorel, according to the 1871 census.

Saint-Pierre de Sorel Church before 1906 (Société historique Pierre-de-Saurel)

Saint-Pierre de Sorel Church before 1906 (Société historique Pierre-de-Saurel)

Alphonse Desjardins (1854-1920) and Dorimène Roy-Desjardins met in Lévis, in the Notre-Dame-de-la-Victoire Parish where they lived only 2 or 3 streets apart. Alphonse was living in Lévis, but worked at Le Canadien, a conservative newspaper in Quebec City. As for Dorimène, she was living with her foster parents and had just finished her studies at the convent.

Since the future bride's parents lived in Sorel, the young couple decided to get married there. On September 1, 1879, the eve of their wedding, they signed their marriage contract at her parent's home in Sorel before notary Louis-Désiré-Eusèbe Cartier. They opted for the "separation as to property" regime. In addition to the family furniture, Alphonse Desjardins granted her as dower the sum of $4,000 in income and, in so doing, rights of survivorship over her husband's property.

The following day, September 2, 1879, Alphonse Desjardins and Dorimène Roy-Desjardins were married before Abbé François-Xavier Lachance in Saint-Pierre de Sorel Church. Alphonse was 24 years old and Dorimène 20. A short time later, the newlyweds settled in Lévis. Their union yielded 10 children: 4 girls and 6 boys.

In 1892, 8 years before the first caisse populaire was founded in Lévis, Alphonse Desjardins was appointed French stenographer at the Ottawa parliament, a position he would hold until he retired in 1917. The job took him away from his family during parliamentary proceedings, which lasted approximately 4 to 6 months a year. As a result, Dorimène saw to the household on her own. She managed the family budget so efficiently that Alphonse Desjardins called her his "Minister of Finance". The title was not ironic but a social practice widespread at the time in working and middle classes, not only in Quebec, but in France and England too.

Dorimène Desjardins played a significant role in the success of caisses populaires. Her contemporaries could not praise her enough, citing several attributes: a sound intelligence, tireless commitment, an orderly mind, lucidity, an unusually strong personality, sound balanced judgement, a natural optimism and innate business sense. These were all put to work in support of the caisse project, bringing continued support to her husband and often being his main source of inspiration. During their 41 years together, she provided him with ongoing support through difficult times. "Too often, I had to raise the spirits of your poor father, faced with so many failures, as you know1", she wrote to her daughter Albertine Desjardins (1891-1968), in the midst of his attempts to obtain legal recognition for caisses in Ottawa.

- Letter by Dorimène Desjardins to her daughter Albertine, Ottawa, undated, cited by Joseph Turmel. "Madame Desjardins, la mère de famille", La Revue Desjardins, XXI, 5 (May 1955), p. 85

Au seuil d'un siècle monument by sculptor Pascale Archambault in Lévis (G. DesRosiers, FCDQ)

Au seuil d'un siècle monument by sculptor Pascale Archambault in Lévis (G. DesRosiers, FCDQ)

Following the establishment of Caisse populaire de Lévis on December 6, 1900, Alphonse Desjardins had to quickly return to Ottawa for the opening session of Parliament. Caisse officers took over responsibility for the caisse. But the time they had available to volunteer was often too short. In 1903, this put Alphonse Desjardins and his associates in a difficult spot. In fact, no administrator offered to replace him as manager, no doubt proof of the scope of the work required. Concerned about building a reserve fund as quickly as possible, Alphonse Desjardins wasn't keen on conferring the task to an accountant. On the verge of despair, he confided his dismay to Dorimène, who spontaneously offered to help him.

When Alphonse Desjardins informed the Board of Directors of Dorimène's offer, they were not entirely surprised. Their daughter Adrienne Desjardins (1888-1965) suggests that in the 3 months preceding the establishment of the first caisse in Lévis, Desjardins and his associates developed the rules and regulations with Dorimène's help. She had since then been of service to the cooperative on many occasions.

Dorimène Desjardins's contribution to the success of the budding enterprise was undeniable. From 1903 to 1906, she acted as manager without officially holding the title, which still belonged to her husband. In 1903 alone, she devoted 33 weeks of her time to Caisse populaire de Lévis accounting. Her involvement continued into 1904 and 1905, all the while devoting a year's worth of time to carry out an even larger task. According to the minutes of Caisse de Lévis Board of Directors meetings, she was authorized to sign all receipts in the manager's name, sign cheques up to $500, deposit available or not immediately needed funds to the financial institutions authorized to receive them, to make, under the supervision of replacement manager Théophile Carrier, loans to regular caisse clients and last but not least, extend temporary advances to members.

The presence of Théophile Carrier as replacement manager should not create an illusion. In everyday practice, Dorimène often performed management tasks in her husband's name, and Carrier's role consisted primarily in putting his signature at the bottom of documents when needed. In recognition of her work, the Board of Directors paid Dorimène the modest sum of $50 a year. This was not compensation for equivalent services rendered, but a token fee for the work performed. In short, Dorimène was in no way a caisse employee.

Her confidence in the caisse project was nonetheless sometimes threatened, as was the case in 1905 when rumours began circulating that bankruptcy could plunge the Desjardins family into insurmountable financial difficulties. Dorimène could not help heeding these claims, particularly since her personal interests were at stake. A change of provincial government in Quebec City had so threatened Alphonse Desjardins's financial security that in 1887, he had resolved to mortgage his home to be able to guarantee his wife the dower agreed to in their marriage contract. If Alphonse Desjardins had to declare bankruptcy, he could lose all of his personal property. And Dorimène could lose as much if not more, considering her dower of $4,000.

Filled with worry, Dorimène Desjardins rushed to Ottawa to share her concerns with her husband. Shaken in turn, Alphonse Desjardins was on the verge of rethinking the entire project. It would take the weight and influence of Msgr. Louis-Nazaire Bégin (1840-1925), Archbishop of Quebec, to convince the Desjardins to pursue their undertaking. Fortunately, all returned to normal in 1906, when the government of Quebec adopted the Quebec Syndicates' Act, a framework law for all cooperative enterprises effectively giving legal recognition to caisses populaires.

In the 9 years that followed, Dorimène Desjardins provided the support required for her husband's work, whether it be publicity, correspondence, founding caisses or accounting. When Alphonse Desjardins showed the first signs of uremia in 1915, a severe renal impairment that would lead to his death 5 years later, it was Dorimène who assisted him, with the help of his daughters Adrienne and Albertine.

The situation changed when Alphonse Desjardins retired in 1917 while developing a project for a federation uniting all caisses populaires throughout Quebec. Dorimène became the middleman for projects spearheaded by her husband, reduced by his illness, and his spokesperson with close collaborators.

Abbé Émile Turmel (1893-1966), curate of Lévis and caisses populaires promoter, reports that between 1918 and 1919, Dorimène Desjardins worked with a special committee created by Caisse de Lévis officers to elaborate on a project for a federation and central caisse conceived by the founder. Moreover, she was the one who asked close colleagues Abbé Philibert Grondin (1879-1950) and Cyrille Vaillancourt (1892-1969), to gather and file "the material that gave rise to Unions Régionales and the Fédération2.

- Fédération des caisses Desjardins du Québec. Projet historique Albert-Faucher, "Abbé Philibert Grondin" files. Letter of Abbé Philibert Grondin to Oscar Gatineau, March 28, 1944.

The Desjardins with their daughter, Albertine Desjardins, on Parliament Hill, Ottawa, in June 1915 (SHAD)

The Desjardins with their daughter, Albertine Desjardins, on Parliament Hill, Ottawa, in June 1915 (SHAD)

The Desjardins with their youngest son, Charles Desjardins, circa 1917 (SHAD)

The Desjardins with their youngest son, Charles Desjardins, circa 1917 (SHAD)

Dorimène Desjardins, surrounded by, left to right, her oldest daughter Anne-Marie, youngest daughter Albertine and granddaugher Cécile Lamontagne, daughter of Anne-Marie and d'Almanzor Lamontagne,

in September 1921. (Collection Claude Laporte, SHAD)

Dorimène Desjardins, surrounded by, left to right, her oldest daughter Anne-Marie, youngest daughter Albertine and granddaugher Cécile Lamontagne, daughter of Anne-Marie and d'Almanzor Lamontagne,

in September 1921. (Collection Claude Laporte, SHAD)

Dorimène Desjardins and her daughter Adrienne in an Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Vallier de Chicoutimi greenhouse in 1921. (Coll. Roger Desjardins, SHAD)

Dorimène Desjardins and her daughter Adrienne in an Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Vallier de Chicoutimi greenhouse in 1921. (Coll. Roger Desjardins, SHAD)

On October 31, 1920, Alphonse Desjardins died at the age of 65, with no caisse succession plan. Since he had exerted strong leadership over the caisses and was the glue that held them together, the caisses populaires had to quickly come up with common structures. From 1920 to 1925, 4 regional unions of caisses populaires were established. But since divergences in the interpretation of the founder's thoughts were beginning to appear, the caisses often called on his widow, who, as a result, acquired great moral authority.

Dorimène Desjardins was the sole heir of the founder's personal papers. Until she died, she had free access to this wealth of expertise and used it to its fullest. Dorimène not only preserved these valuable archives, but also ensured the conservation and availability of all the documents on the subject of cooperation, the social economy and public affairs in her husband's personal library. In 1921, she set out to donate the documents to Caisse populaire de Lévis, but the attempt fell flat. Two years later, she sold the documents—nearly 1,000 titles—to Bibliothèque de la Législature, now Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée nationale, in Quebec City. In doing so she achieved 2 goals, since the library was patronized primarily by Quebec City society.

During this time, Dorimène Desjardins's important role in the caisse populaire movement came to full light. According to Quebec City's L'Action catholique, "She simply continued playing her role. It became clearer and apparent to all just to what extent she had been valuable to the flourishing endeavour3."

During the 1920's, Dorimène Desjardins worked toward the unification and organization of caisses populaires in the Quebec City area. Again according to Abbé Turmel, she played an active role in the foundation of the Union régionale des caisses populaires Desjardins du district de Québec in 1921. In a show of thanks, she was named vice patron of the Board of the Union, conferring upon her the status of honorary member. The honorary title was not simply for decorum. The patron of the Board was none other than Cardinal Louis-Nazaire Bégin of Quebec City and the honorary president Msgr. François-Xavier Gosselin, Curate of Notre-Dame-de-la-Victoire Parish in Lévis.

- "Mort de madame Alph. Desjardins", L'Action catholique, June 14, 1932, p. 10.

Joseph-Kemner Laflamme (FCDQ)

Joseph-Kemner Laflamme (FCDQ)

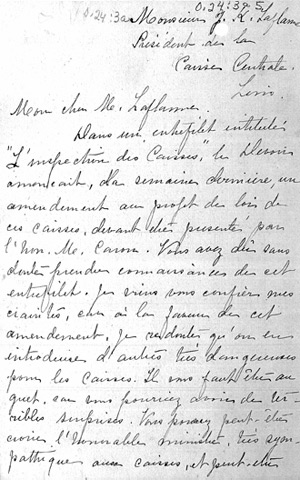

Letter of March 10, 1925, by Dorimène Desjardins to J.-K. Laflamme (FCDQ)

Letter of March 10, 1925, by Dorimène Desjardins to J.-K. Laflamme (FCDQ)

A few years later, Dorimène Desjardins intervened in the debate surrounding the establishment of a central caisse, a kind of central caisse populaire in charge of clearing cheques for local caisses and managing their excess liquidity on a regional or provincial level. A brief recall of the facts: In the summer of 1923, caisses populaires in the Quebec City area had approved a project to found a regional central caisse in Lévis.

Elected president of Union régionale de Québec in October 1923, Joseph-Kemner Laflamme (1884-1926) convinced his fellow administrators that the central caisse should instead be of provincial scope. To speed up the goal, they considered pairing it to Caisse populaire de Lévis which already played a suppletive role in the matter, and taking over the caisse to this end. But they came up against a refusal from Dorimène and Alphonse's oldest son, Raoul Desjardins (1880-1951), who, as president and manager, fiercely defended the Lévis caisse's prerogatives.

Annoyed, Laflamme decided to invoke the moral authority of Dorimène Desjardins. In a letter dated April 16, 1924, he outlined the project, asking if all was consistent with her late husband's thinking. Laflamme also reminded Dorimène that that as "necessary associate" of the founder's work, only she could "point out what path he would have taken4". A few days later, Dorimène supported the project, and tried to bring the 2 opposing parties together. But nothing would do. Undermined by internal dissent, Caisse centrale Desjardins de Lévis, founded in 1924, would never attain provincial scope.

At the time, Dorimène Desjardins was an avid reader of L'Action catholique and Le Devoir. With regards to the caisses populaires, she was particularly interested in the debate surrounding verification and farm credit problems.

On March 5, 1925, Le Devoir devoted a paragraph to caisse verification. In it, she learned that Joseph-Édouard Caron (1866-1930), Quebec Minister of Agriculture, would soon introduce a bill in which caisses populaires would be subject to annual verifications by regional union inspectors.

Upon reading the news, Dorimène was stung to the quick. True to her husband's vision, she was not as much opposed to independent inspections of caisses populaires as to any attempt by the state to intrude in internal matters. On March 10, 1925, she took the initiative of writing to Joseph-Kemner Laflamme, still President of Union régionale de Québec, to warn him to be cautious, even wary, of any government interference. In this particular case, she begged him to accept no government subsidy whatsoever, either directly or indirectly.

Dorimène was also concerned about Union catholique des cultivateurs and its president, Laurent Barré (1886-1964), who she suspected was lobbying Minister Caron for government-based agricultural credit. On this matter, she shared the concerns of L'Action catholique, who feared such a measure would turn the caisses into government banks. She took a stand in the debate by supporting agricultural credit based on the promotion of savings and caisse populaire business development. The verification bill was passed a few days later.

Dorimène's work extended to caisses populaires supervision. In January 1926, Abbé Émile Turmel, Secretary of Union régionale de Québec, reminded her that the institution would always "happily welcome any comment you'd like to make in the interest of caisse verification and the direction local caisses should take5".

- Fédération des caisses Desjardins du Québec. Fonds Alphonse-Desjardins, 0.24:3a1. Letter of Joseph-Kemner Laflamme to Dorimène Desjardins, April 16, 1924.

- Fédération des caisses Desjardins du Québec. Fonds Alphonse-Desjardins, 0.24:3a4. Letter of Abbé Émile Turmel to Dorimène Desjardins, January 14, 1926.

Dorimène Desjardins surrounded by members of her son Paul's family in Ottawa. (Coll. Roger Desjardins, SHAD)

Dorimène Desjardins surrounded by members of her son Paul's family in Ottawa. (Coll. Roger Desjardins, SHAD)

Dorimène Desjardins died on June 14, 1932, at the age of 73. Caisses populaires organized a stately funeral for her in Lévis. L'Action catholique stated that her demise marked "a sad day for French Canada", as she was unarguably "one of the most informed women on economic issues as seen from a social standpoint". In vibrant tribute, the paper added that "without her, there probably would be no Desjardins caisses populaires6."

From this standpoint, there is enough tangible evidence of Dorimène Desjardins's work to be able to consider her the co-founder of caisses populaires.

- "Mort de madame Alph. Desjardins", loc. cit.

September 17, 1858

Marie-Clara Dorimène Roy-Desjardins is born in Sorel.

Circa 1865 - Circa 1875

She attends Notre-Dame-de-Toutes-Grâces convent (today Marcelle-Mallet School) in Lévis.

September 2, 1879

Dorimène Roy-Desjardins and Alphonse Desjardins get married in Saint-Pierre de Sorel Church.

1880

Dorimène Desjardins gives birth to her first child, a son named Raoul. She will have 9 other children, the last one in 1902.

1892-1917

Alphonse Desjardins is the French stenographer for Ottawa House of Commons debates, which takes him away from Lévis an average of 6 months a year.

December 6, 1900

A meeting is held at which the Caisse populaire de Lévis is founded.

January 23, 1901

Opening of the Caisse populaire de Lévis, the head office of which is in the family home.

March 11, 1903 - November 14, 1906

In Alphonse Desjardins's absence while at work in Ottawa, Dorimène Desjardins takes over caisse management with no title or salary in addition to overseeing the household.

Spring 1905

The Desjardins go through difficult times because of their exposure to financial risk since Caisse populaire de Lévis has no legal recognition.

March 5, 1906

The Quebec Legislative Assembly passes the Quebec Syndicates's Act, giving legal recognition to caisses populaires.

1918-1919

Dorimène Desjardins contributes to the work of a committee put in place by Caisse populaire de Lévis on a project for a federation and caisse centrale conceived by Alphonse Desjardins.

October 31, 1920

Alphonse Desjardins dies in Lévis, his last 6 years overshadowed by illness.

1921

Dorimène Desjardins helps organize and create Union régionale des caisses populaires Desjardins du district de Québec.

1923

She is named vice patron (honorary member) of the board of Union régionale des caisses populaires Desjardins du district de Québec.

April 23, 1924

She supports a project to establish a caisse centrale of provincial scope.

May 8, 1924

Caisse centrale Desjardins de Lévis is founded.

March 10, 1925

Dorimène Desjardins takes a stand in the debate surrounding agricultural credit favouring the option of credit based on people's savings and the development of caisses populaires.

June 14, 1932

Dorimène Desjardins dies in Lévis at age 73.

Source: Société historique Alphonse-Desjardins, June 2012