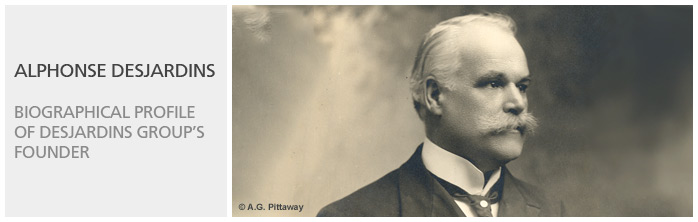

Alphonse Desjardins (1854-1920)

Desjardins ad

Collège de Lévis in 1893 (Collège de Lévis)

Collège de Lévis in 1893 (Collège de Lévis)

Gabriel-Alphonse Desjardins was born on November 5, 1854, in Lévis, across from Quebec City. He was the eighth of 15 children in a family of modest means. His father, François Roy "dit" Desjardins, was a day worker who never managed to hold a job for long. His mother, Clarisse Miville "dit" Deschênes, had to work for neighbours as a housekeeper to make ends meet.

Alphonse Desjardins attended Collège de Lévis. From 1864 to 1870, he completed the 4-year commercial course, and 1 year of the Latin course. His academic records show him to be a dedicated, diligent student. He did not let the fact that he had to repeat the third year of the commercial course discourage him. Instead, he was one of the first in his class and won many awards. The same went for the first year of the Latin course.

In addition to receiving a few awards, he was selected as a candidate for Académie Saint-Joseph, a society that rewarded the efforts of deserving Collège de Lévis students. Often absent from class, the young Desjardins became an average, inconsistent student, since family support began to run dry. In July of 1870, at age 15, he was forced to leave school, probably because of the cost of a classical education was just too steep.

For a quarter of a century, Alphonse Desjardins followed in the footsteps of his older brother Louis-Georges Desjardins (1849-1928), a journalist, military man and Conservative politician. In the summer of 1869, he enlisted in Lévis's 17th Battalion, Volunteer Infantry where Louis-Georges held the rank of warrant officer. After attending the Military School of Quebec in 1870, Alphonse Desjardins was promoted to the rank of sergeant-major. On October 17, 1871, the young non-commissioned officer set out for Red River in Western Canada as part of an expedition against the American Fenians, a revolutionary group fighting for the independence of Ireland. But his military career was short-lived.

Back in Lévis, he became a member of the conservative press. In 1872, he found employment at L'Écho de Lévis where he learned the basics of reporting. The following year, the paper sent him to Ottawa as correspondent. There, he sought out new experiences, in both playwriting and mutuality as it applies to homebuilding. But his projects remained in the planning stages.

When L'Écho de Lévis ceased publication on July 12, 1876, Alphonse Desjardins went to work for Le Canadien, a Quebec City daily of which his brother Louis-Georges had recently become co-owner. His contributions to the paper were many. In addition to short news items, he occasionally reviewed the British press's coverage of all aspects of daily news, and wrote a column on local Lévis news. In practice, the young journalist's primary task was soon dictated by the needs of the moment. In 1877 and 1878, Le Canadien's editorial team assigned him to cover the debates in the Quebec Legislative Assembly. There, he demonstrated on-the-job skills that won him the esteem of his colleagues in the press gallery. On June 19, 1879, they made him a member of the executive committee of Association des journalistes de la province de Québec.

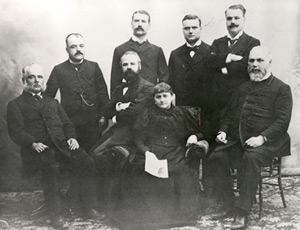

On the far right, Alphonse Desjardins (standing) and Louis-Georges (seated) with their brothers and sister in 1896 (SHAD)

On the far right, Alphonse Desjardins (standing) and Louis-Georges (seated) with their brothers and sister in 1896 (SHAD)

Lévis in 1881 (Collège de Lévis)

Lévis in 1881 (Collège de Lévis)

Alphonse Desjardins's work as a reporter opened doors for him in Quebec City society. On December 15, 1877, he was one of the founding members of Société de géographie de Québec. He was also active in the Conservative Party. In 1878 and 1879 he was on the management committee of Club Cartier de Québec, a Conservative political club. As a consequence, he acted as secretary of Comité central conservateur du comté de Lévis in the federal elections of fall 1878.

His political commitment earned him the position of editor of the proceedings of the Quebec Legislative Assembly. His job consisted in summarizing the members' speeches and reporting their main points in Débats de la Législature de la Province de Québec, an annual publication subsidized by the government.

Ready to raise a family, Alphonse Desjardins married Marie Clara Dorimène Roy-Desjardins (1858-1932) in Sorel on September 2, 1879. The couple had 10 children, 6 boys and 4 girls.

In the 1880s and until the mid-1890s, Alphonse Desjardins was active in various associative networks active in Lévis society. He became deeply involved in Lévis cultural organizations devoted to literary and patriotic topics such as Institut canadien-français, of which he was president in 1883, and Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. He was also involved with charitable and philanthropic organizations such as Société Saint-Vincent-de-Paul and Congrégation des Hommes de Notre-Dame de Lévis. In so doing, he became a member of several networks, which he would put to good use when the time came.

During the same period, his work with Chambre de commerce de Lévis gave him an opportunity to take part in a series of initiatives aimed at local city development. He was an attentive witness to the debate regarding the lack of a lending institution in Lévis. Following the footsteps of his brother Louis-Georges once again, he was on the board of Chambre de commerce de Lévis, first as secretary-treasurer from 1880 to 1888, and then as advisor until 1893.

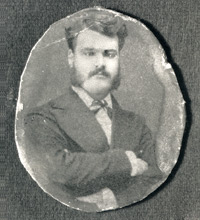

Alphonse Desjardins, circa 1879 (CPDL)

Alphonse Desjardins, circa 1879 (CPDL)

The Parliament of Quebec before the fire of 1883 (BANQ)

The Parliament of Quebec before the fire of 1883 (BANQ)

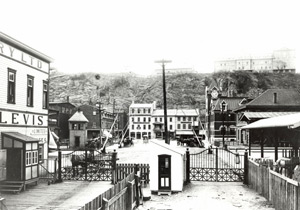

Lévis, circa 1912 (BANQ)

Lévis, circa 1912 (BANQ)

The Ottawa Parliament before the fire of 1914 (BANQ)

The Ottawa Parliament before the fire of 1914 (BANQ)

Alphonse Desjardins continued to quietly edit the parliamentary debates. But in 1887 the situation changed when the Liberals, headed by Honoré Mercier (1840-1894), took power. Immediately, the Liberals considered taking the parliamentary debates away from Alphonse Desjardins to give them to another editor. He overcame these difficulties, but only for a time. On December 14, 1889, he learned that the Mercier government would no longer underwrite the publication of debates in an effort to reduce public expenditures. Clearly, a partisan motive lay behind these budgetary considerations. It is said that Alphonse Desjardins's refusal to make substantive changes to his report of a debate on funding for the inter-provincial conference of 1887, at the request of Honoré Mercier or one of his close collaborators, was the reason publication was halted. The "Desjardins debates" were published for the last time in winter 1890.

Overnight, Alphonse Desjardins found himself unemployed. Forced to make a career shift, he decided to return to journalism. On July 9, 1891, in Lévis, he launched a new daily, L'Union canadienne, in which he supported the program of the federal Conservative party. A true one-man band, he was both owner and publisher. But health problems forced him to cease publication of the paper on October 10, 1891, after only 3 months.

For the last time in his lifetime, Alphonse Desjardins used partisan politics to make a career shift. From 1890 to 1893, he was secretary of the Provincial Conservative Association in Lévis. In the winter of 1891, he worked for the Conservative party for the federal election. The Conservative government in Ottawa sought a way to reward the long-term activist. On April 22, 1892, the federal Parliament adopted a report from the debate committee recommending the appointment of Alphonse Desjardins to the position of French stenographer at the Ottawa House of Commons. He would hold the position until he retired in 1917. Wishing to keep his residence in Lévis, he resigned himself for 25 years to spending 6 months a year in Ottawa, 450 kilometres from his family. This new life helped him regain his interest in insurance and mutuality.

In 1893, he compiled notes for a study of life insurance in Notes pour servir à une étude sur l'assurance-vie. He also carefully studied the workings and activities of existing mutual aid societies in Lévis, in particular the local branch of Société des Artisans canadiens-français, opened in 1889, and Société de construction permanente de Lévis, founded 20 years earlier. From 1892 to 1895, he sat on the management board of the latter, which provided mortgages to its members. A tireless individual, he still found a way to teach stenography at Collège de Lévis from 1893 to 1900 in between parliamentary sessions in Ottawa.

In 1897, Desjardins heard, in the House of Commons in Ottawa, a debate that brought him awareness of the devastating effects of usury1. On April 6, Michael Quinn (1851-1903), Conservative member from Montréal-Sainte-Anne, introduced a bill to prevent usurious practices. Quinn cited, by way of an example, the case of a Montreal man who was sentenced to pay interest charges of $5,000 on an initial loan of $150. Stunned, Desjardins began to search libraries for a solution. The following year, he came across a work entitled People's Banks by British author Henry William Wolff (1840-1931), president of the International Co-operative Alliance. He immediately contacted the author and a long correspondence between the two men began. Wolff agreed to introduce Alphonse Desjardins to various European cooperators.

Little by little, Alphonse Desjardins launched into a serious investigation of cooperation on an international scale. His main considerations were the social issues in Quebec. He saw the social devastation caused by industrialization, rural exodus, unemployment and emigration to the United States. In his opinion, the scourge of usury was only one of many telling example of the social problems. He criticized the government's inability to bring about effective reform, while neither the labour movement nor socialism could propose viable alternatives. Association and local development were at the heart of Desjardins's thinking, as well as the influence of Church social doctrine and the social economy in the same line of thought as the encyclical letter Rerum Novarum (On the Condition of Workers) by Pope Leo XIII (1810-1903).

1. The practice of lending money at unreasonably high interest rates

Site where the first caisse was founded in 1900 (FCDQ)

Site where the first caisse was founded in 1900 (FCDQ)

The caisse populaire model is essentially a synthesis of 4 people's savings and credit systems: credit unions, the Schulze people's bank, the Raiffeisen rural lending bank, and most of all, the Luzzatti people's bank. Alphonse Desjardins's sources of inspiration were therefore basically European. He then took into account the North-American environment and experience, and defined a new type of institution adapted to the Quebec and Canadian context.

The readiness with which Alphonse Desjardins adopted the cooperative model can in large part be explained by the fact that he saw several points of convergence between the European cooperative experience and his own, acquired in Lévis's associative networks. In his European counterparts, he found values and organizational principles he had already experienced in various Lévis institutions. This is why he was easily able to make modifications to the European models and propose a new, original one.

After long, fruitful research in 1898 and 1900, Alphonse Desjardins came to the conclusion that the solution to social issues lay in a cooperative association. His caisse populaire model, whose operations were limited to the parish, was the first step in his cooperative project organization plan. His goal was not only to fight against the problem of usury; he also want to empower the working classes, give them the means to manage their own capital without interference from the state, develop the habit and desire to save, and finally, make credit more widely available.

The Desjardins family residence in 1906 (FCDQ)

The Desjardins family residence in 1906 (FCDQ)

On December 6, 1900, Alphonse Desjardins saw the crowning of all his efforts. Over 130 citizens were present at the founding of Caisse populaire de Lévis, the first savings and credit cooperative in North America, which launched its activities in January 1901. At the end of the first day, the amount collected came to only $26.40. A very modest start.

The first few years, most transactions were made either in the Desjardins family home, which housed the Caisse head office, or in the hall of the Lévis branch of Société des Artisans canadiens-français. Over the next 5 years, only 3 other caisses were founded: Saint-Joseph de Lévis in 1902, Hull in 1903 and Saint-Malo à Québec in 1905.

In the meantime, Caisse populaire de Lévis made fast progress thanks to the work and selfless devotion of Alphonse Desjardins, the support of the Lévis clergy, in particular the priests at Collège de Lévis, the quiet and effective work of local mutualists and the ongoing, willing collaboration of his wife, Dorimène Desjardins. In addition to keeping up the family home, Dorimène Desjardins oversaw Caisse business affairs. Between 1903 and 1906, she managed the Caisse, without title or salary, during her husband's extended stays in Ottawa.

Photo taken on March 5, 1907, by Lord Grey, Governor General of Canada from 1904 to 1911, during a visit to Caisse populaire de Lévis, of which he became a member (BANQ)

Photo taken on March 5, 1907, by Lord Grey, Governor General of Canada from 1904 to 1911, during a visit to Caisse populaire de Lévis, of which he became a member (BANQ)

For more than 5 years, Desjardins made several repeated attempts to set up a legal framework for his caisse populaire project with both the provincial and federal governments. Early on, his preference was for the adoption of a federal law that would allow him to establish caisses populaires in all Canadian provinces. Shortly after Caisse populaire de Lévis was founded, he first approached the federal government, who lent a deaf ear.

To achieve their goal, Alphonse Desjardins and his associates would have to exert strong pressure on the federal government. Desjardins engaged in an intense propaganda campaign aimed at the public authorities. At first, he sought international recognition. In 1904, he became a member of the International Co-operative Alliance, which granted him the privilege of having membership as an individual. He would remain a member until 1910. But Alphonse Desjardins's efforts were mostly focused within the country. In 1904, for example, he founded L'Action populaire économique, an association devoted to expanding the realm of people's economic organizations and lobbying governments to pass legislation recognizing caisses populaires. But nothing would do and Ottawa refused to budge. Somewhat reluctantly, Desjardins turned to the Quebec government in 1905.

That year, Desjardins's initial attempts led to further delays. Exhausted by the wait, Alphonse and Dorimène were also more than a bit disappointed since their family was highly vulnerable to the risk associated with the legislative gap surrounding the caisses populaires. In the spring of 1905, on the verge of despair, the couple considered abandoning their project. Members of the Lévis clergy, particularly Msgr. Bégin (1840-1925), Archbishop of Quebec, encouraged them to persevere.

Things started moving in 1906. On March 5, the Quebec Legislative Assembly unanimously passed the Quebec Syndicates' Act, which received royal assent 4 days later. Upon hearing the long-awaited news, Alphonse Desjardins rejoiced. The caisses populaires had finally received legal recognition.

Alphonse Desjardins did not abandon his goal of having a law passed by the federal government. He continued to believe that the provincial law's scope was too regional and only provided a provisional guarantee. He made yet another attempt with the help of Jacques-Cartier Conservative MP Frederick Debartzsch Monk (1856-1914), at the time in parliamentary opposition, who, on April 23, 1906, introduced to the House of Commons the Act respecting industrial and co-operative societies.

This time he met with success. Between December 18, 1906, and April 11, 1907, the House of Commons Special Committee in charge of studying the project heard several testimonies, including very favourable comments from Governor General of Canada and Honorary President of the International Co-operative Alliance, Lord Earl Grey (1851-1917). The committee recommended the government pass the measure. Less than a year later, on March 6, 1908, the House of Commons unanimously adopted the bill regarding cooperation.

The Senate, however, defeated the bill by a single vote on July 15 of the same year, on the grounds that it would infringe on the powers of the provinces. The result, no doubt, of a nationwide opposition campaign led by the Retail Merchants' Association of Canada, whose primary function was to prevent the development of consumer cooperatives. This new setback marked the end of Desjardins's efforts on the federal level. Until 1914, a few MPs would try to get legislation on cooperation passed, but to no avail. Faced with the federal government's inertia, Alphonse Desjardins would have to make the most of the provincial law, even if its scope seemed somewhat limited.

In Quebec, however, the legal recognition of caisses populaires had the effect of opening the floodgates. The years from 1907 to 1915 were the most active of Alphonse Desjardins's entire lifetime. During this time, he criss-crossed Quebec to help found and develop caisses populaires. His most devoted associate is Abbé Philibert Grondin (1879-1950), a priest at Collège de Lévis, who conducted a publicity campaign in the Catholic press. Between 1909 and 1920, he wrote at least 300 newspaper articles, almost all devoted to caisses populaires, in La Vérité and occasionally in L'Action sociale (which would become L'Action catholique in 1915), 2 mass-circulation papers in Quebec City. In 1910, he also published Catéchisme des caisses populaires, a booklet that through questions and answers presented all necessary information about the goals, organization, and functioning of caisses populaires.

For his part, Alphonse Desjardins spent his time personally and promptly answering the many requests for information he received every day. He was also available for public lectures, speeches and talks. He produced a large body of work including pamphlets and newspaper and magazine articles on the topic of cooperation in general terms, and savings and credit cooperatives in specific terms.

As the founder, Alphonse Desjardins orchestrated, with the help of a handful of close collaborators, the budding caisses populaires movement. His involvement was such that he, in some ways, played the role of a federation. His publicity campaign promoting the caisses grew considerably. In 1908 alone, he travelled approximately 5,380 kilometres throughout Quebec to accept a variety of invitations. He gave 52 public lectures and over 150 talks. He also received 2,500 letters, often requiring detailed answers.

Philibert Grondin, author of

Catéchisme des caisses populaires (SHAD)

Philibert Grondin, author of

Catéchisme des caisses populaires (SHAD)

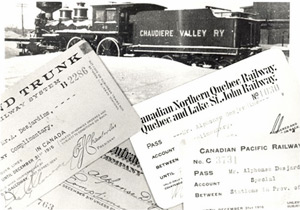

A few of Alphonse Desjardins's train tickets (SHAD)

A few of Alphonse Desjardins's train tickets (SHAD)

Quebec City Archbishop Msgr. Louis-Nazaire Bégin (BANQ)

Quebec City Archbishop Msgr. Louis-Nazaire Bégin (BANQ)

In his work promoting caisses populaires, Alphonse Desjardins was carried by a social dynamic that allowed him to build a considerable social network. Despite initial reservations on the part of a few members of the high clergy, several bishops, in particular Msrg. Bégin of Quebec, actively supported Desjardins's work. Generally speaking, he preferred to receive explicit support from local priests before establishing a caisse populaire in their parish. He also invited the priests to take on the administration, even the management of the caisse. In several parishes, parish priests were the real organizers of caisses populaires.

Overall, the clergy responded favourably to the call launched by Alphonse Desjardins, but support was not unanimous. Convinced of the benefit the caisses populaires could bring to their faithful, several bishops recognized the caisses populaires as a Catholic social undertaking, which they recommended to their clergy's attention. Desjardins's reputation spread all the way to the Vatican. On April 12, 1913, a representative of Msgr. Bégin, Archbishop of Quebec, delivered to Alphonse Desjardins papal letters from Pius X (1835-1914), naming him Commander of the Order of St. Gregory the Great to reward him for his civil merit and contribution to Catholic social action.

Desjardins also used informal networks within the parish community as a foothold. Women were called upon to play a key role in his cooperative project. On a higher level, he could count on, crucial at the time, the support of organizations attached to the Catholic Church in Quebec: Action sociale catholique, Association catholique de la jeunesse canadienne-française, Ligues du Sacré-Cœur, École sociale populaire, social action diocesan committees, as well as agricultural and land settlement cooperatives.

Generally speaking, the clergy gave him direct and enthusiastic support, with a steadiness and efficiency dependent, however, on its priorities, as well as cyclical ups and downs. The clergy apart, Desjardins recruited the most ardent promoters of the caisses among nationalists such as Henri Bourassa (1868-1952) and his associate Omer Héroux (1876-1963) of newspaper Le Devoir, established in 1910. In comparison, he received only circumstantial support from unions and fraternal benefit societies. Over the years, Alphonse Desjardins's cooperative project gained recognition through the Catholic press, of course, but also by word of mouth, from one parish to another, finally expanding to all 4 corners of the province.

All of this support was very helpful to the caisses populaires, since Desjardins faced serious opposition, in particular from the Canadian Merchant's Association and the National Bank, who viewed the caisses as competitors.

Building on this social network, the caisses populaires soon became widely known. As of 1909, Alphonse Desjardins was swamped with invitations from people who wanted to set up a caisse in their own parish. From 1907 to 1915, he founded no fewer than 136 caisses in Quebec alone. He also corresponded regularly with many caisse managers, providing advice and encouragement, which allowed him to supervise their operations from a distance.

Alphonse Desjardins accomplished all this in his free time in between parliamentary sessions in Ottawa, with no financial assistance whatsoever. He often thought up various scenarios that would allow him to get a government grant to help finance supervision and guidance services, for which he would be responsible. But the fear of interference from the state in caisse internal affairs prevented him from making any such request.

Alphonse Desjardins's reputation and renown grew to the point that he received invitations and requests for information from several Canadian provinces, but Ontario was the only province to which he personally extended his activities. After helping establish a sector caisse in 1908 for federal civil servants in Ottawa, he founded 18 caisses populaires in French-Canadian parishes between 1910 and 1913. His influence also extended to English Canada on a more intellectual level, since, because of his experience, he was regarded as a specialist in his field. His most voluminous correspondence was with George Keen (1869-1953), General Secretary and Treasurer of the Co-operative Union of Canada, founded in 1909.

The same went for the United States. Alphonse Desjardins visited the U.S. 5 times between 1908 and 1912. In addition to founding a dozen caisses populaires and credit unions, mostly in Franco-American parishes, he had a profound influence on cooperative legislation in several states. In Massachusetts, New York, New Hampshire and North Carolina, bills that led to the creation of credit unions drew liberally from the caisses populaires model and Quebec legislation.

As of 1914, Alphonse Desjardins was forced to cut back on his activities due to illness. Incurable uremia sent him into lengthy and frequent periods of convalescence between brief bouts of remission. In 1917, he had to give up his duties as House of Commons stenographer after 25 years of service. The threat of impending death made him consider creating a federation and central caisse to unite and strengthen the caisses populaires network and ensure his work endured. He had developed an action plan in that regard at least 10 years earlier.

Based on the European cooperative experience, he wanted to bring local caisses populaires together within a provincial federation that would be responsible for publicity, supervision and verification. In addition, a central caisse would administer local surplus funds held by local caisses and provide loans to those short of funds. Afraid of losing their autonomy, caisse officers did not take well to the idea, especially because of major issues surrounding the federation's financing and the division of power. Aware of the issues, Alphonse Desjardins proposed, on July 3, 1920, a preliminary meeting of all caisse representatives to study the project. But his days were numbered.

Portrait of Alphonse Desjardins at a presentation given in Boston (SHAD)

Portrait of Alphonse Desjardins at a presentation given in Boston (SHAD)

Alphonse Desjardins in 1919 (La Lumière)

Alphonse Desjardins in 1919 (La Lumière)

On October 31, 1920, Alphonse Desjardins died in his home in Lévis, a few days shy of his 66th birthday. He was buried on November 4, 1920, following a stately funeral attended by several representatives of the Church and both governments. There were at that time some 140 caisses active in Quebec, with total assets of $6.3 million and 31,000 members.

Alphonse Desjardins left behind to his fellow citizens an instrument of cooperation and local development designed to meet the needs and aspirations of parish communities. When paying posthumous tribute to the founder of caisses populaires, several newspapers heralded the economic and social scope of his work. After designating Alphonse Desjardins as "one of the great benefactors of his race", Quebec City's L'Action catholique predicted that the caisses would become "the solid base of the French Canadian national fortune". In a similar frame of mind, Le Devoir stated that his name would remain "one of the major initiators and first artisans of the cooperative movement in Canada".

November 5, 1954

Gabriel-Alphonse Desjardins is born in Lévis. He is the eighth child of the Roy "dit" Desjardins couple. Of the 15 children born of their union, only 8 reach adult age.

1864-1870

Alphonse Desjardins completes the commercial course at Collège de Lévis, and the first year of the Latin course.

1869-1872

Alphonse Desjardins enlists in Lévis's 17th Battalion, Volunteer Infantry and participates in an expedition in Red River, Manitoba, against the American Fenians, a revolutionary group fighting for the independence of Ireland.

1872

Alphonse Desjardins starts working at L'Écho de Lévis where he learns the basics of reporting.

1876

When L'Écho de Lévis closes, he begins working for Le Canadien, a Quebec City daily co-owned by his brother Louis-Georges.

1879-1889

Alphonse Desjardins records the proceedings of the Legislative Assembly of Quebec.

September 2, 1879

He marries Dorimène Roy-Desjardins (1858-1932) in Sorel. The couple has 10 children between 1880 and 1902, 3 of which die at an early age.

1880-1893

Alphonse Desjardins sits on the board of Chambre de commerce de Lévis first at secretary-treasurer until 1888 and then as advisor.

July 9, 1891 - October 10, 1891

Publishes the newspaper L'Union canadienne, but health problems force him to cease publication after only 3 months.

April 22, 1892

Alphonse Desjardins is appointed French stenographer at the Ottawa House of Commons.

April 6, 1897

At the House of Commons, Alphonse Desjardins hears the "tragic testimony" of Michael Quinn on loan-sharking. In the months that follow, he begins doing research on cooperatives.

May 12, 1898

Alphonse Desjardins writes his first letter to Henry William Wolff (1840-1931), British cooperator, author of People's Banks and president of the International Co-operative Alliance, who puts him in touch with various European cooperators.

1900-1914

He takes several steps to obtain legal recognition for caisses populaires in Ottawa, but to no avail.

December 6, 1900

The Caisse populaire de Lévis is founded, the first savings and credit cooperative in North America.

January 23, 1901

Caisse populaire de Lévis operations begin.

1904

Alphonse Desjardins becomes a member of the International Co-operative Alliance, which grants him the privilege of having membership as an individual. He would remain a member until 1910.

December 21, 1904

Alphonse Desjardins founds L'Action populaire économique, a "propaganda organization" whose goal is to "promote the development of all people's economic organizations".

March 5, 1906

The Quebec Syndicates Act is passed unanimously by the Legislative Assembly and receives royal assent 4 days later.

1907-1915

In his travels, he personally helps found 136 caisses populaires in Quebec. He also establishes a sector caisse and 18 other caisses in French-speaking Ontario.

1908-1912

Alphonse Desjardins visits the United States 5 times. He founds approximately 12 caisses populaires and credit unions, all in Franco-American parishes. He also helps draft bills that lead to the creation of credit unions in 4 states.

1910

Publication of Le Catéchisme des caisses populaires, authored by Abbé Philibert Grondin, under the pseudonym J.-P. Lefranc. A brochure entitled La comptabilité des Caisses Populaires, authored by Alphonse Desjardins, is published the same year.

April 12, 1913

A representative of Msgr. Bégin, Archbishop of Quebec, delivers to Alphonse Desjardins papal letters from Pius X (1835-1914), naming him Commander of the Order of St. Gregory the Great to reward him for his civil merit and contribution to Catholic social action

1914

Alphonse Desjardins's doctor diagnoses him with uremia, a serious illness. He is forced to cut back on his activities.

1917

Alphonse Desjardins leaves his job as French stenographer for the House of Commons after 25 years of service.

July 3, 1920

Alphonse Desjardins sends caisses populaires a circular letter in which he presents an outline of his plan for a federation and central caisse, while recommending a preliminary meeting with all caisse representatives.

October 31, 1920

Alphonse Desjardins dies in his home in Lévis, a few days shy of his 66th birthday.

Source: Société historique Alphonse-Desjardins, June 2012